Despite recession, crime keeps falling:

In times of recession, property crimes, in particular, are expected to rise.

They haven’t.

Overall, property crimes fell by 6.1 percent, and violent crimes by 4.4 percent, according to the six-month data collected by the FBI. Crime rates haven’t been this low since the 1960’s, and are nowhere near the peak reached in the early 1990’s.

Who expected crime to increase? Did you? I did. But I didn’t know anything about crime statistics over time so I was working off naive intuition. Did social scientists expect this? I recall a lot of worry in the media about a year ago that the crime drop which started in the 1990s would be reversed, and I shared the worry. Here’s Matt Yglesias worrying last January:

I think this is worth worrying about. One thing we know about crime is that when wages and employment levels for low-skill workers are high, crime goes down. Another is that mass incarceration works – increase the number of beds in prison and the number of sentence-years handed out and the crime rate drops. But the first of these is the reverse of what happens in a recession, and the second we’ve already pushed well past the limit of cost-effectiveness (see here) and it’s inconceivable to me that you could actually push this far enough to compensate for the declining economy in the context of declining state budgets.

It’s easy to find national uniform crime reports data back to 1960, and unemployment rates. Quick correlations between 1960-2008 are:

Violent Crime Aggregated 0.37

Murder 0.52

Rape 0.37

Robbery 0.53

Assault 0.24

Property Crime Aggregated 0.53

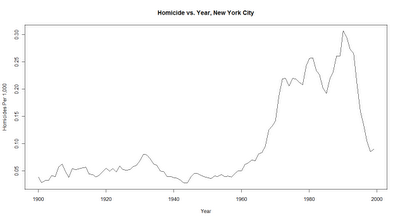

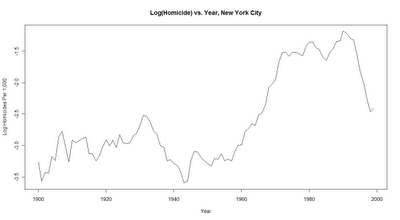

One seems to see a modest expectation for a rise in crime then over this time period. But poking around the ICPSR I came across Eric Monkkonen’s data sets on homicide in New York City going back to the 19th century. Below are homicides per capita by year between 1900 and 2000. The second chart is log-transformed.

It seems that there’s another “Depression Paradox” here. The economic distress of the Great Depression seems to have been associated with less crime, while the economic exuberance of the 1920s led to more crime. So if I constrained the time series from 1920-1940 the correlations might be quite different.

All things equal the recent past is a better guide to the near future than the less recent past. But it’s important to remember that history does sometimes work in cycles, and the deeper past can occasionally give us insights which the recent past can not. One could construct a tentative model whereby basal crime rates reflect cultural norms, and once norms and crime hit a particular “equilibrium” it may take a bit of a “shock” for it to shift out of the stable state.