Peter Frost on Roman Britain:

Historians often assume that the Romans changed Britain politically but not demographically. The indigenous elites adopted Roman culture while the mass of the population remained Celtic. When the Anglo-Saxons arrived in the fifth century, much of this population fled to Wales and Cornwall, where they would retain their language and traditions. Meanwhile, those who remained behind were obliterated through a process of ethnic cleansing and coerced assimilation.

This historical account may be false….

…

Once Rome had pulled its troops out of Britain in the early 5th century, there was no longer an inflow of people to offset the demographic deficit. The local population fell into decline, and the decline accelerated in the 6th century when plagues killed three out of every ten people. The Romano-British needed no help from the Anglo-Saxons to die out. They did it largely on their own.

Peter’s summation of the historical consensus is correct. This view is exposited in Norman Davies’ The Isles. The historians have had a bias for several generations of assuming that population movements have been marginal in shaping cultural change. In some cases this is correct; I’ve looked and it is very difficult to detect a discontinuity among the Hungarians in relation to their neighbors despite this nation’s putative origins among an Inner Asian group (and later settlement of Turks who fled the Mongols within the Magyar kingdom). The emergence of Hungarian is therefore most plausibly modeled as a process of elite emulation, where Romance, German and Slavic speaking peasants adopted the speech and identity of their Magyar overlords. The Hungarian case is easy to test because the geographical distance of the Magyar homeland in the Volga-Ural region is great enough that they would have been a genetically distinct population who would introduce alleles which couldn’t be explained except as exogenous inputs (the Hazara are a case of this).

The question of Britain is a bit more confused. Historians rely on textual evidence which points to Anglo-Saxon rule of Celtic-speaking populations in their kingdoms in the 7th and 8th century, in particular stipulations of different wergild (‘blood money’) for Saxons, noble and commoner, and Celts, noble and commoner. The existence of an elite Celtic speaking class suggests that Gildas’ allusions to genocide were exaggerations. Over the past 10 years a lot of exploration of the genetic variation within Britain has simply muddied the picture. Though some early Y chromosomal studies suggested sharp breaks between Wales and England, autosomal data don’t seem to show this. Rather, a reasonable model is that the Anglo-Saxons contributed a significant, but minority, element to England’s contribution. Their genetic impact drops as a decaying function of the distance from East Anglia, which was the heart of the “Saxon Shore,” but their cultural influence was not diluted along the wave of advance. This highlights the stark difference between genetic and cultural inheritance, the former is constrained in the nature of transmission in a way the latter is not. In fact, during the high tide of the Viking era in Britain’s history, the Saxon redoubt was Wessex, which genetic data show seem to has been minimally affected by German settlement. Rather, Wessex was likely conquered by the Saxonized.

Finally, what happened to multicultural Britain? The genetic data show a small effect, a random African lineage here and there which can not be explained by recent genealogy. An orders of magnitude less important than the Saxon migration. I think the reason is the simple that that urban areas were population sinks, and unless immigrants “went native” they disappeared into the genetic black hole. A reasonable historical analogy may be Lithuania. After the official union of the political structures of Lithuania and Poland in the 16th century the Lithuanian nobility was Polonized. The emergence of modern Lithuanian identity was to a great extent an elevation of Lithuanian peasant culture, which was left unaffected by Polonization. If extant literary or high cultural artifacts are used to reconstruct Lithuania’s history one might posit that Lithuanian’s disappeared in the early modern era, only to reemerge in the 19 century due to the ideology of nationalism.

There has long been a supposition that Latinization in Britain was relatively restricted and superficial compared to Gaul, where Celtic speech seems to have disappeared in the 5th century. This may be a inference made plausible by hindsight, because Britain was one region (the Balkans the other) where the ornaments of Roman high culture was totally extinguished in the face of barbarian invasions. By contrast, Gaul, Iberia and Italy all produced culturally hybrid elites who were Romanized. But from what I know the archaeological evidence does suggest a shift even among Romano-British warlords from a Roman to a British style in their material possessions over the 5th and 6th centuries (additionally, Roman commanders and legions stationed in Britain had a tendency to relocate to the continent in part because that was where the “action” was in terms of advancement and glory, so there may have been a sorting process whereby the most Romanized elites emigrated, while those who were willing to become barbarized, whether by going back to their Celtic roots, or becoming Saxonized, remained).

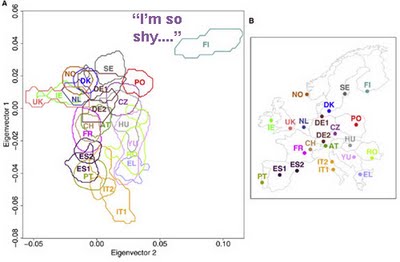

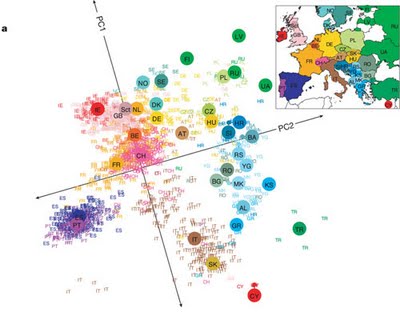

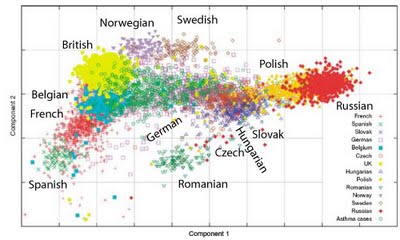

Here’s some gene related charts to support what I’m saying above about the muddle. On first inspection a Netherlandish affinity to many Briton’s is obvious (also, you can see it in Structure). Uniparental markers show the clines I’m alluding to above though, so where these samples come from within Britain matters a great deal at the scale we’re talking about. But the main problem is that some might argue that there have long been interactions between the low countries and southeast England because of their proximity, and not one particular Anglo-Saxon migration. Perhaps at some point it will be feasible to analyze the decay linkage disequilibrium (or see if there’s linkage disequilibrium) in southeast England to date the time of a putative admixture event. But of course the peoples of the North European Plain and those of England are relatively close genetically, so I’m not going to hold my breath. Ancient DNA will probably yield more sooner.