One of the mantras of the new age is that European nations have to deal with diversity, something that’s new to them. This actually ahistorical. Some military units in the Austro-Hungarian Empire actually used English as the lingua franca because of their ethnic diversity (due to those who returned from the United States, see 1848: Year of Revolution), while the French language and identity as dominant within the political unit of France is an artifact of the 19th century (see The Discovery of France: A Historical Geography). But one point which was brought home to me was the diversity of the United Kingdom in 1800. I knew of course that Ireland before the famine was 1/3 of the population of the United Kingdom, but I hadn’t thought through the political ramifications. In The Cousins’ Wars: Religion, Politics, Civil Warfare, And The Triumph Of Anglo-America Kevin Phillips highlights an important set of facts about the United Kingdom:

1) The constant migration of dissenting Protestants in the 17th to 18th century to America resulted in a firming up of the position of the Anglican mainstream within England.

2) The massive migration (as well as deaths due to famine) of Irish Catholics in the 19th century solidified the Protestant character of the United Kingdom.

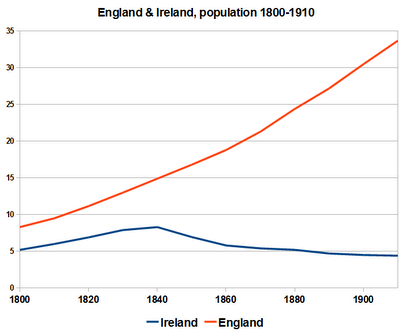

Below the fold is a comparison of England and Ireland in terms of population between 1800 and 1910.

Here is the biography of Patrick Kennedy, great-grandfather of John F. Kennedy:

By the time Patrick reached adulthood, both his parents were apparently dead and the family homestead was controlled by his older brother John Kennedy, more than a dozen years Patrick’s senior, who was already married and the father of four children. The eldest son normally inherited whatever claims existed to the family’s farm. Because of the life-threatening scarcity of food and resources, the rest of the children, such as third son Patrick Kennedy, usually were expected to leave for the New World. Patrick also had a brother James and a sister Mary.

Patrick’s life as a farmer in Dunganstown consisted mainly of cutting and tying bundles of grain by hand, and planting and tilling potatoes for his family’s consumption. This routine varied only when he ventured into the nearest town, New Ross, with supplies of barley, and when the family attended mass about a mile away.

At the age of 26, Kennedy decided to leave Ireland. It is assumed this was for reasons of starvation related to the Irish Potato Famine, illness, or because he knew that a third-born son had virtually no hope of running his family’s farm. His good friend at Cherry Bros. Brewery in New Ross, Patrick Barron, who taught Kennedy the skills of coopering, had come to that conclusion months earlier and left for America. In October 1848, in love with Barron’s cousin Bridget Murphy and with a plan to wed, Patrick Kennedy decided to follow.

Note: I am aware of the fact that some of the decrease in Ireland’s population and England’s rise is due to emigration from the former to the latter. Removing this would not change the qualitative relation much.