First, thanks to Zack for the opportunity to blog here. More importantly, thanks to Zack for the Harappa Ancestry Project! I’ve learned a lot from him in terms of the optimal way to go about “genome blogging,” and have been able to benefit from his experiences in my own African Ancestry Project. It’s really great that in 2011 we don’t have to wait for academic researchers to explore the topics which interest us at the intersection of genetics and history.

Prior to being interested in South Asian genetics on such a fine-grained level I had read works such as Nicholas B. Dirks’ Castes of Mind. To give you a sense of Dirks’ argument, here’s the summary from Library Journal:

Is India’s caste system the remnant of ancient India’s social practices or the result of the historical relationship between India and British colonial rule? Dirks (history and anthropology, Columbia Univ.) elects to support the latter view. Adhering to the school of Orientalist thought promulgated by Edward Said and Bernard Cohn, Dirks argues that British colonial control of India for 200 years pivoted on its manipulation of the caste system. He hypothesizes that caste was used to organize India’s diverse social groups for the benefit of British control. His thesis embraces substantial and powerfully argued evidence. It suffers, however, from its restricted focus to mainly southern India and its near polemic and obsessive assertions. Authors with differing views on India’s ethnology suffer near-peremptory dismissal….

One of the inferences which people draw from this model, perhaps unfairly, is that the endogamy and biological separation of caste groups is relatively new, and that genetic variation is likely to be arbitrarily distributed across caste groups. The most extreme interpretations almost seem to turn the British into the culture-creators of all that is Indian. In any case, genetics can obviously test the power of this thesis in relation to ancestry.

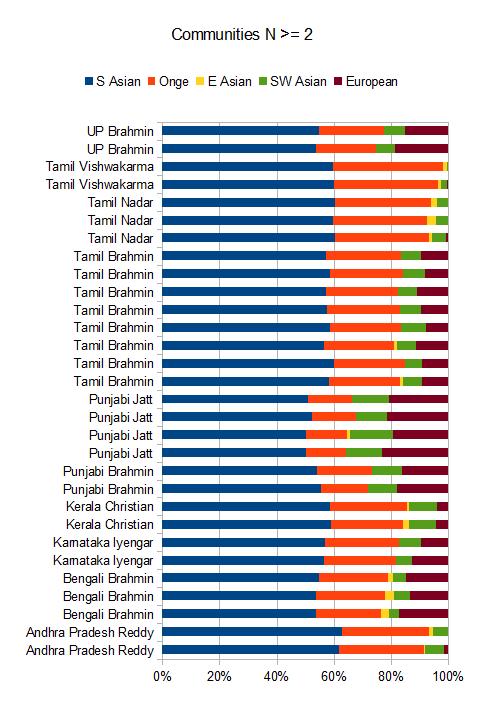

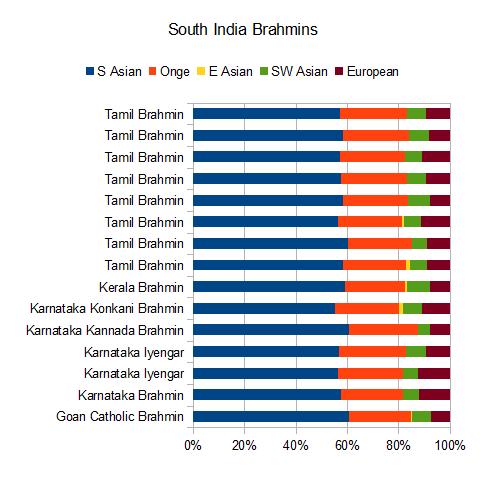

First up, below I have taken all the HAP samples where N >= 2. I’ve done some semantic shifting, so that “Tamil Iyer” becomes “Tamil Brahmin.” I know that some of you have more information about the samples than is listed in Zack’s spreadsheet, but I’ve been conservative. I will also use the word “community” sometimes instead of “caste” in future posts, because I don’t know what the proper word for Syrian Christians or Bihari Muslims would be. But really same difference to me. I want to focus on groups with caste/religious labels intersected with a specific region here. The bar plot below is not going to be a surprise, and you see the clusters in Zack’s dendograms, but I thought it would still be useful.

Caste is not genetically arbitrary. To me this strongly falsifies any contention that the endogamous units which we know as castes (or jatis) derive predominantly from the past 200 to 300 years. Tamil Brahmins number in the millions, so it does not seem that they plausible that could have expanded so rapidly from a very small homogeneous founder group two to three centuries ago. Rather, their origins are almost certainly more ancient. Some of the results are also not that surprising. Northwest Indians have the genetic profile you’d expect in comparison to other groups. The Bengali Brahmins consistently have more of an “East Asian” trace than other Brahmin groups, while Tamil Brahmins seem elevated in the “SW Asian” fraction in relation to other Brahmins. Both of these trends I think illustrate the likelihood of some admixture with location populations.

Now let’s look within regions a bit. I’ll divide South Asia into four quadrants. The classification will be self evident from the bar plots.

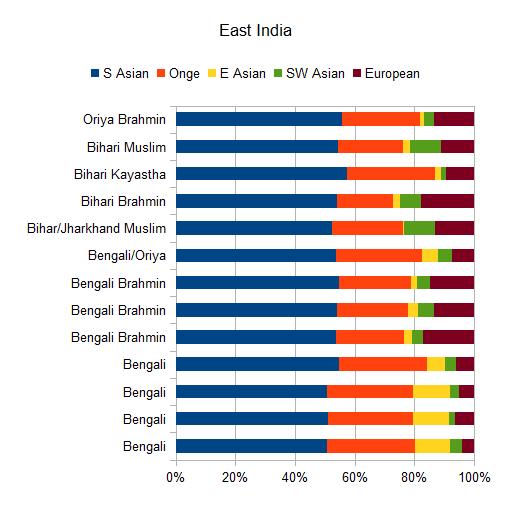

I’m the third to last Bengali, while the last two are are my parents. My parents are not related, and from opposite ends of Comilla east of the Padma. My mother is the last bar plot, and from a family with attested Middle Eastern ancestry (non-South Asian focused ADMIXTURE runs tend to bring the small, but non-trivial, element out more clearly). I believe that that is what is elevating her “SW Asian” fraction. It is notable that the two other individuals from eastern India who show this balance between “SW Asian” and “European” are also of Muslim background. I doubt that that is coincidental. Though South Asian Muslims are overwhelmingly indigenous, they do seem to have some outside admixture since the arrival of Arabs, Persians, and Turks, to the subcontinent. The most obvious marker of this to me isn’t the elevation of “SW Asian,” but the common presence of African ancestry among Pakistani Muslims. This certainly is due to the arrival of Africans and people of part African origin in the retinues of Indo-Islamic rulers.

Aside from this it seems more clear to me now that like in South India the Brahmins of the east are also relatively new and intrusive. All show an elevation of “European,” though the trace of “East Asian” suggests admixture. That probably indicates their arrival after the absorption of the Mundari populations, and perhaps Tibeto-Burmans, into the substrate of eastern India.

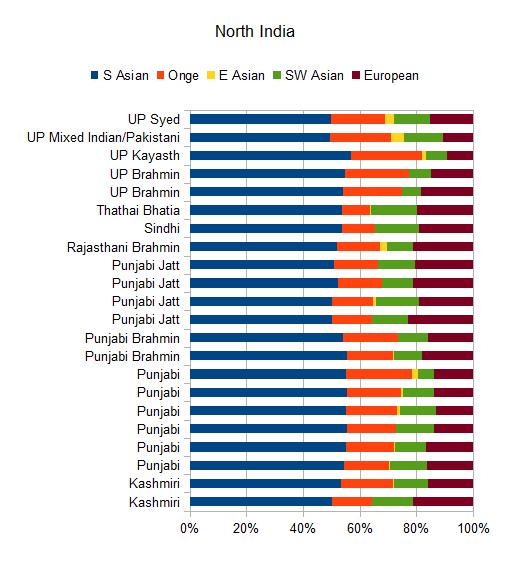

I find nothing important to say here aside from the fact that we need a lot more samples for UP! The UP Kayastha indicates that there’s a fair amount of variation here which is not being sampled.

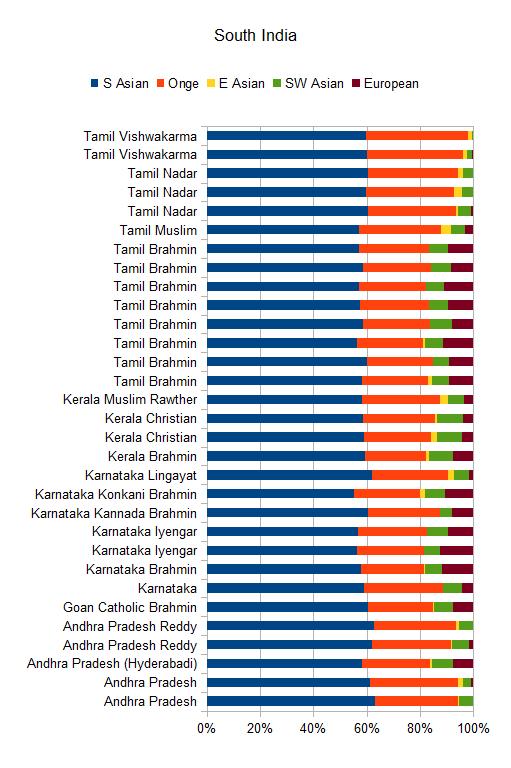

We are obviously rich in samples from South India. One interesting aspect is the bias toward “SW Asian” as opposed to “European” among non-Brahmins, especially what I think are termed “Forward Castes” (e.g., Reddy). The proportions are low, but consistent. This is the inverse of what we see among non-Brahmins in East India. I am liable to dismiss the the East Asian admixture among many South Indians, especially non-Brahmins, as noise, but it may be signatures of absorbed Mundari substrate. Who knows? The Kerala Christian samples have the most “SW Asian.” We need better references from other non-Brahmin non-tribal/Dalit castes in Kerala (a Nair is coming up), but I wonder if this validates the idea of some Semitic admixture of yore among Nasranis (or, perhaps just as likely long term trade and marriage connections over the centuries).

Now let’s just look at South Indian Brahmins.

Very similar, huh?

Finally, the last cluster in western India:

Not much to go on, though I’ve been told that several of the Gujaratis are Patels.

Overall I think we can reject a strong recent post-colonial social construction of caste as a plausible model going by genetics. What replaces it? There probably won’t be a neat model. But hopefully as HAP expands it can fill in some of the gaps. The 1000 Genomes Project will be releasing Assamese Ahom, Bengali Kayasthas, Marathas from Maharashtra, and Punjabis from Lahore, this year.